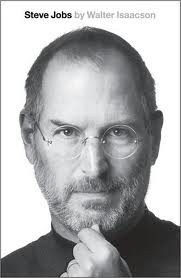

Walter Isaacson has done so much media in support of his biography of Steve Jobs that I feel like I’ve heard him read every part of the book except the ISBN and the chapter titles. Everyone, probably even including Isaacson, wishes that the release of the book didn’t unhappily coincide with Jobs’ death, but it did and that adds extra poignancy to the work. It didn’t hurt sales.

Some of the interviews with Isaacson have been better than others, of course and the quality of the interviewer usually dictates the quality of the interview. This is what separates the dreadful Ann Curry from Charlie Rose to cite just one egregious example. Terry Gross of NPR and WHYY is one of the best in her field, at least in part owing to the fact that she has an hour to fill and can let her guest take time to develop and expand on their ideas. Her guests really get to express themselves.

So I was surprised that after all these interviews and all this time with Jobs and thinking about his subject, Isaacson is wrong on an essential element of what made Jobs and Apple as successful. Here’s Isaacson and Gross on the October 25th airing of Fresh Air:

GROSS: Now why did he want Apple to have its own operating system, one that would only run on Apple products?

ISAACSON: Jobs was an artist. It was like he didn’t want his beautiful software to run on somebody else’s junky hardware, or vice versa; for somebody else’s bad operating system to be running on his hardware. He felt that the end-to-end integration of hardware and software made for the best user experience. And that’s one of the divides of the digital age because Microsoft, for example, or Google’s Android, they license the operating system to a whole bunch of hardware makers.

But you don’t get that pristine user experience that Jobs as a perfectionist wanted if you don’t integrate the hardware, the software, the content, the devices, all into one seamless unit.

GROSS: So how did this work for and against Steve Jobs?

ISAACSON: It was not a great business model, at first, to insist that if you wanted the Apple operating system, you had to buy the Apple hardware and vice versa. And Microsoft, which licenses itself promiscuously to all sorts of hardware manufacturers, ends up with 90 to 95 percent of the operating system market, you know, by the beginning of 2000.

But in the long run, the end-to-end integration works very well for Apple and for Steve Jobs because it allows him to create devices that just work beautifully with the machines, for example the iPod, then the iPhone, then the iPad. They’re all seamlessly integrated. (emphasis added)

So in the year 2000, I think Microsoft probably had 10 times the market value of an Apple, but Apple surpassed Microsoft a year or so ago and is now the most valuable company on Earth by doing this integrated model. (emphasis added)

But that’s not right. As James Surowiecki of The New Yorker points out in the October 17th issue of the magazine, it was ultimately Jobs’ willingness to allow others to use the platform and his precious products that made Apple the company that Isaacson recognizes as one that has transformed six and maybe seven industries and become the biggest market cap company in the world. Apple left to itself was a 5% market share player. Once it opened its platform, it was through the roof. Sure it was partly because the products were great, but it doesn’t happen without the help of those outside Apple to make those products better. Here is Surowiecki:

When Jobs returned [after having been fired], he still wanted Apple to, as he put it, “own and control the primary technology in everything we do.” But his obsession with control had been tempered: he was better, you might say, at playing with others, and this was crucial to the extraordinary success that Apple has enjoyed over the past decade. Take the iPod. The old Jobs might well have insisted that the iPod play only songs encoded in Apple’s favored digital format, the A.A.C. This would have allowed Apple to control the user experience, but it would also have limited the iPod market, since millions of people already had MP3s. So Apple made the iPod MP3-compatible. (Sony, by contrast, made its first digital music players compatible only with files in Sony’s proprietary format, and they bombed as a result.) Similarly, Jobs could have insisted, as he originally intended, that iPods and iTunes work only with Macs. But that would have cut the company off from the vast majority of computer users. So in 2002 Apple launched a Windows-compatible iPod, and sales skyrocketed soon afterward. And, while Apple’s designs are as distinctive as ever, the devices now rely less on proprietary hardware and more on standardized technologies.

The iPhone signalled a further loosening of the reins. Although Apple makes the phone and the operating system itself, and although every app is sold through the App Store, the system is far more open than the Mac ever was: there are more than four hundred thousand iPhone apps written by outside developers. Some are even designed by Apple’s competitors—you can read on the Kindle app instead of using iBooks—and many are so inelegant that Jobs must have hated them. Such apps make the iPhone messier than it would otherwise be, but they also make it much more valuable. The old Jobs might well have tried, in the interest of quality, to contain the number of apps: he always talked about how saying no to ideas was as important as saying yes. Though Apple does vet apps to some extent, the new Jobs essentially said, Let a thousand flowers bloom.

The introduction of the iPad has ratified this new reality, since developers have already released more than a hundred thousand apps for the tablet. The result is that the network effects that worked against Apple in the eighties, making it essentially a boutique company, are now working in its favor: the more apps Apple’s products have, the more people want to use them, which, in turn, makes developers want to develop for them, and so on.

Yes. That makes perfect sense to me. It’s a wonder that Isaacson missed it by such a wide margin.

Posted by Mark Wegener

Posted by Mark Wegener